Hi everyone. Thanks to Irving Berlin for this week’s title. Here I am, starting with the weather again. I struggle to write in this exceptional heat, mostly because I am listless and even tapping at the laptop seems like an effort too far. But the rising temperatures did get me thinking about those writers who did a lot of their writing in hotter climates, especially in the days when there was little technological assistance to cope with the heat—limited electricity, no air conditioning, inadequate fans etc. How did they do it? Here are a few things I found out:

Freya Stark (1893-1993) travel writer, explorer, and photographer spent years living in and travelling around the Middle East. Stark didn’t just endure the heat, she walked straight out into it—often riding on a camel straight out into it—and often wrote from tents pitched in deserts or temporary lodgings in Syria, Iraq, and Iran. In The Valleys of the Assassins and her collected letters, she makes vivid reflections on how extreme heat shapes and reshapes time and thought. At midday, the desert shimmered into oblivion. Writing was often impossible until the evening wind cooled the sand. Yet such a testing environment wasn’t a hindrance to her—it was part of her purpose, to bring this part of the world to her readers. Stark seemed to treat the heat as a force that helped her to strip Middle Eastern life down to its essentials and convey this back to the cool and comfortable British public. Her writing schedule followed local rhythms: early-morning note-taking, long afternoon siestas, and late-night reflections. She wrote by the light of a kerosene lamp, with insects droning outside and sweat smudging the pages.

Gertrude Bell (1868-1926), another remarkable British writer, was a key figure in British imperial politics and Middle Eastern archaeology. Her letters, reports, and travel books are both historical documents and deeply personal records of writing under pressure—geopolitical and environmental. She often wrote in intense heat while traveling through Iraq, Syria, and the Arabian Peninsula. In one letter from Baghdad in July 1920, she described temperatures above 45°C and the ink drying so fast on the page her words disappeared as she wrote them. She simply carried on—documenting her travels, drawing maps, and penning long political memos with purpose and clarity. These days we don’t have to worry about ink disappearing and preserving our writing—everything we have ever written online is saved forever in the deep dark mystery that is the internet. (I don’t know whether we should be grateful for that not-so-small mercy, or not). Bell’s approach was utilitarian and disciplined, she relied on strict routines. She kept journals, wrote daily letters, and maintained detailed archives—all while often ill, under stress, and soaked in perspiration. The heat was acknowledged but never used as an excuse. Her writings are a testament to determination, rigour, and intellectual focus—even when writing from a windblown tent in 45°C sandstorms.

Agatha Christie (1890-1976) is best known for her crime mysteries, and some of her most atmospheric novels were written—or at least conceived—under the heat of the desert sun. Christie spent long periods in the Middle East, especially in Iraq and Syria, accompanying her second husband and best beloved, the archaeologist Max Mallowan on digs. She used these hot and dusty travels as rich material. Murder in Mesopotamia, Death on the Nile, and Appointment with Death were all inspired by—and in part written within—the shimmering, heat-hazed isolation of archaeological sites. Christie didn’t simply tolerate the heat as background; she excavated it for narrative tension. Sun glare, heat exhaustion, sweaty and dusty strangers appearing on camels often foreshadow sinister happenings. She developed practical coping mechanisms; writing in the early morning, and retreating to shaded verandas when possible. In her autobiography, she jokes about candles melting and ink smearing in the heat, and typewriter keys sticking—but the novels got written all the same.

I’m sure I read somewhere once that Vita Sackville-West (1892-1962) went underground—literally—during her time in what was Persia. Sensibly, she wrote in underground rooms during the hottest parts of the day. If true—and I can’t find a reliable reference right now—these spaces would have been cooler, naturally temperature-controlled, and provided a consistent environment for Vita and her papers. If our heatwave summers are becoming a regular thing then maybe a cool cellar will become the writing room of choice?

Lots of writers simply got up very early, before the heat set in: Isak Dinesen (Karen Blixen) writing from her coffee farm in Kenya started writing before dawn; Graham Greene in Sierra Leone stopped at 500 words every day, presumably he got them rattled out before it got too hot; Somerset Maugham—whom I always think of as writing on a verandah under a swaying palm with a pink gin at his elbow—used specially selected thick, absorbent paper when writing in the tropics. In the high humidity standard paper would become so damp it was near impossible to write on. Maugham’s smart choice meant he could write at pretty much any time of day without being troubled with soggy pages. And I have my own theory about Ernest Hemingway’s propensity to write standing up—as well as helping his concentration and engagement, it avoided a sweaty bum and sticking to the chair caused by sitting for long periods in the Havana and Florida steaminess! The discipline they all kept of writing before the heat set in was central to their productivity.

Virginia Woolf(1882-1941) is perhaps most often used as an example of a British writer sensitive to her environment. In her diaries and letters, she lamented how heat drained her intellectually. In July 1934, she wrote: “The heat is so intense one can hardly think, much less write.” The heat would sap her energy and destroy her focus. Her solution was to escape. The Woolfs owned Monk’s House in Rodmell, Sussex, where Virginia would retreat during hot months. The countryside offered some relief from the stifling air of London, though not always enough. On particularly hot days, she’d limit herself to short bursts of writing in the morning before retreating into the garden or heading to the river Ouse for the cooler riparian air. Still the close atmosphere of heat made its way into her writing. In The Waves and To the Lighthouse, the heat is used not just as setting, but as emotional climate—oppressing, shimmering, unrelenting. In The Waves she wrote that "the sun rose higher. Everything lay deep in heat, still as a painting." You can almost feel the thickness of the air, the closeness.

When I think of Orwell, I picture grey skies and wartime gloom (I’m not a big fan). But Orwell spent significant time in hot places—colonial Burma, and civil war–era Spain. In Spain, Orwell wrote in near-impossible conditions. He described sleeping in clothes “crawling with fleas,” (infinitely worse than a bit of prickly heat), temperatures soaring by midday, and the sun burning down on makeshift writing tables in stone farmhouses. The heat wasn’t just physical—it seemed to intensify his political anxieties and observations. Another one for unyielding discipline, he set rigid routines, wrote early, and didn’t let weather (or illness) get in the way of the work.

Before air conditioning was widely available, writers got creative about keeping cool. Marcel Proust, suffering from asthma and heat sensitivity, had his bedroom entirely cork-lined (as you do) to muffle sound and stabilise temperature. He famously wrote from bed, often with the shutters closed against sun’s glare. (Don’t try the cork-lined thing at home. Although in the 1970s I remember cork-lined kitchens…). And Paul Bowles, writing his merciless novel The Sheltering Sky under merciless sun in Marrakesh, would hang wet sheets in front of the windows to cool any breeze coming in. (Now, this is a good idea. I recommend a wet flannel on the chest when trying to sleep during hot nights, and a wet towel around the neck à la Wimbledon players is also good).

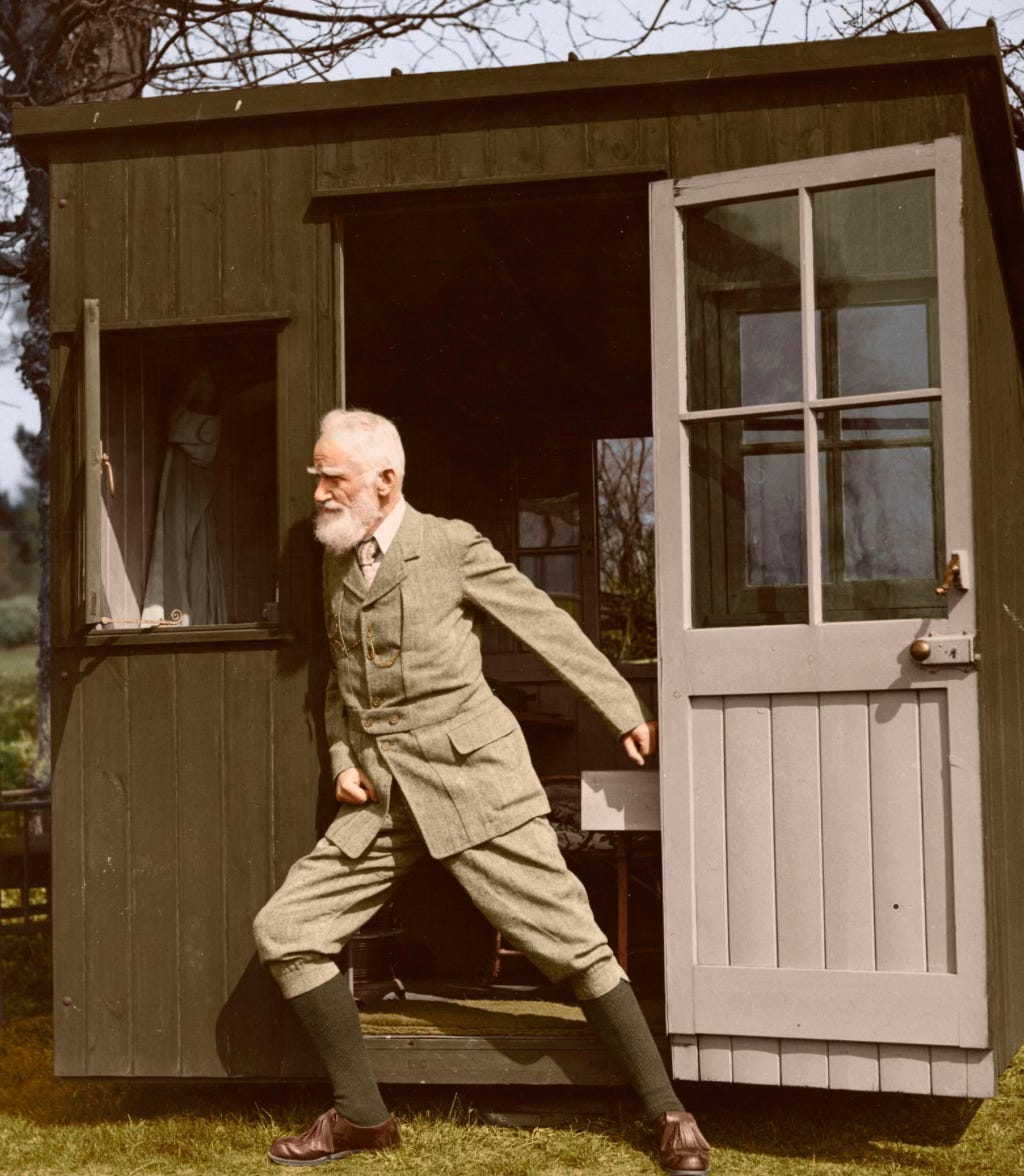

Ann Bridge (1889-1974), during her diplomatic postings in Peking (Beijing), developed what you might call an early form of mobile writing. She created what she termed her “morning room” - a meticulously positioned space in a large room that caught cross-breezes from a careful arrangement of screens and open windows. As the sun moved throughout the day, so did Bridge, shifting her writing desk to maintain optimal shady and breezy conditions. I think George Bernard Shaw had something similar in concept—a garden summerhouse writing studio that could be rotated to follow the path of the sun. However, his plan was to stay in the sunny warmth rather than trying to keep out of it. I guess the sun in Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire doesn’t quite compare to that in Beijing, or Singapore, or Cuba—except for this week, of course, when it is rivalling Hell itself. And here is Shaw, putting his back into rotating the shed….and, as always, (NOT) dressed for the heat. Did Shaw actually have any clothes other than a green tweed suit and gaiters?

Alan Bennett (A National Treasure) provides an endearing portrait of how you might cope with heat and still produce great writing. In his Diaries and essays, Bennett frequently mentions the discomfort of writing in heat from his London home or Yorkshire retreat. His approach? A blend of humour and practicality. Linen suits, early writing sessions, and simple food. (These are strategies I favour myself—the loose linen frock, iced tea in the fridge, living on chilled watermelon and mini Magnums). The heat would often become part of the anecdote—“the sort of heat that renders thought difficult and pudding unnecessary,” as he once wrote. Can’t you just hear him saying that in his slow Yorkshire accent? Although I would count a mini Magnum as a necessary pudding.

Every summer lately it seems the same battle returns: long golden days promising time to write productively, and then heat slams the brakes on good intentions. If you’ve ever stared at a notebook or a blank screen, hot and irritable, mind melted, wondering how writers ever got anything done in hot weather—you're in good company. British authors, especially those writing before air-conditioning and ergonomic fans, often found themselves wilting in their rooms or adventuring in deserts and Mediterranean villas. Yet they kept writing—sometimes complaining, sometimes adapting, and sometimes bringing the heat right into their prose. These days, even in hotter and steamier climes, we can open a notebook and use a biro (or something equally convenient but a little more stylish) for our notes and observations on the go. Or we can repair to an air-conditioned room and a laptop whilst sipping a Singapore Sling or a Long Island Iced Tea. Even here, in the good old sweltering UK, we have fans, and cold showers, and ice cubes and mini Magnums. We aren’t forced to get up in the middle of the night (unless about to miss a deadline), or to test different inks against the desert heat, or order in reams of specially prepared paper, or repurpose our suncream to unstick sticky typewriter keys. So if, like me, you’re blaming less than perfect conditions for writing apathy, then get a grip—if nothing else, it can give you something to write about!

I’d love to know how you’re keeping writing in the current heatwave. But for now, that’s all. Keep as cool as you can, and I’ll write again soon. Take care. x.

It’s not at all elegant, but I was so hot yesterday afternoon I put some frozen peas on my feet!

It is blissfully cooler today, thank goodness! Yes, I just sat and waited for it to be over. A lovely post, June, and I am enjoying Ann Bridge, which is perfect holiday reading.